We will talk about how, throughout the years, art referenced the hopes and fears connected to the key events of industrial revolutions. We will take a look at pieces showing both the destruction of the environment, and the beauty of will nature; both the process of subduing nature, and a harmonious co-existing.

On top of this, we will try to analyse and evaluate the examples and possibilities of using art to familiarise society with scientific discoveries and technological advancements, as well as to increase people's awareness about their potential consequences. We wish to talk about, among others: paintings of Belle Époque, which were both enthusiastic and wary of the widespread electrification; Soviet mosaics portraying the nuclear power of the USSR; artists taking note of how the condition of the environment has worsened due to industrial interferences, acknowledging the harm, and appealing for protection of nature; the dangers of mythologising the technical advancements, and of too much ambition, or maybe even a lack of responsibility on the human part.

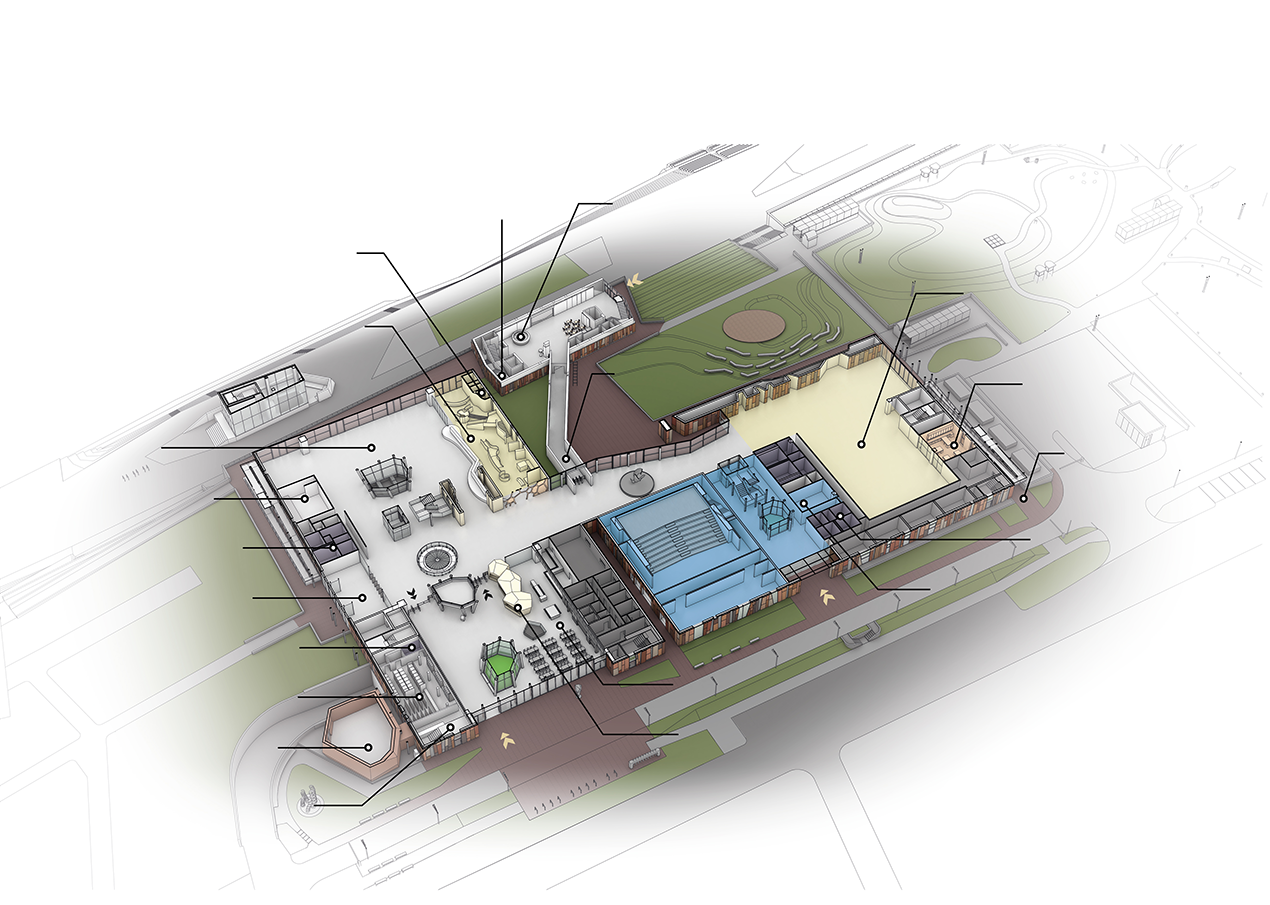

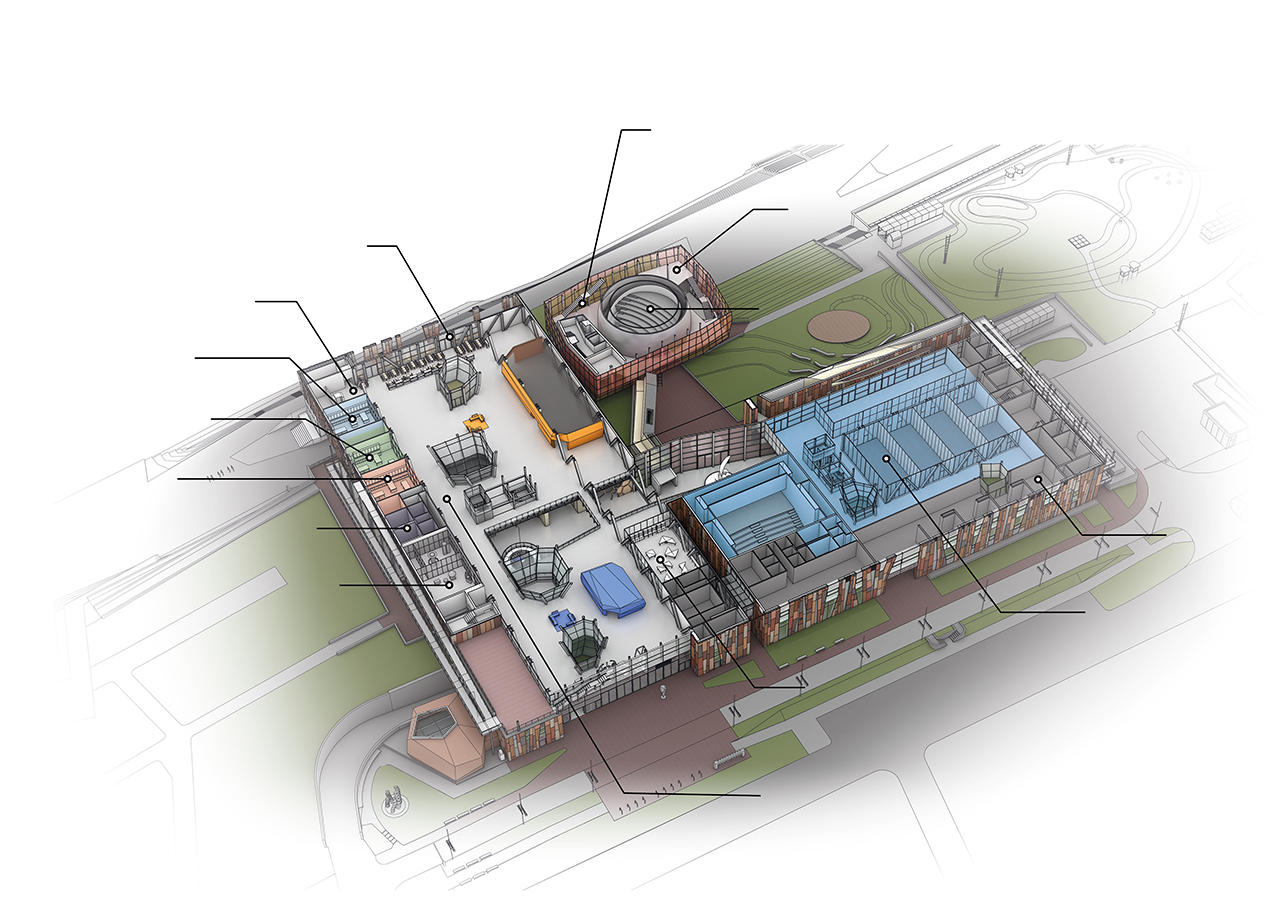

Gallery of change

The English poet, author, artist, mystic, and a predecessor of romanticism, William Blake, portrayed Isaac Newton in a rather unusual way. It is definitely not a classic portrait. Newton is shown like a Greek god. Muscular, beautiful, nude, staring into a diagram that he's drawing with a compass. It could seem like a sort of apotheosis, we know however, that Blake was critical towards Newton's only having eyes for science. And well, it's true that Newton, fully focused on the compass, can't notice the beautiful, colourful rocks and the see around him. He ignores them completely. Nature isn't important to him. The real world isn't important to him.

Maybe Blake, who lived at the time of galloping industrialisation, has also felt like a uncritical belief in the human power, resulting from further scientific discoveries and technical solutions, could in turn cause a shift away from nature and a plundering exploitation of the environment. Meanwhile, science also works to warn against what Blake was worrying about. Thankfully, an increasingly better understanding of the mechanisms of natural world allows us to protect it more efficiently, and counter the harm done by humanity.

Paradoxically, the science-dazzled Newton and nature-loving Blake might be actually on the same page. After all, science is about the observation and admiration of nature. And even if science takes away the myths, and makes nature seem less romantic, both science and poetry can be used in a very similar way – to grasp the world's beauty

Emily Carr was a Canadian artist and author, inspired by the cultures of First Nations from the North-West Coast of North America. Her paintings, from the 1940's, the last decade the artist was alive, clearly show her growing anxiety about the industry influence of the British Colombia natural environment. Carr's works from the time mirror her fears about increasingly frequent logging, its ecological impact, and the consequences for Canada's indigenous population.

In her painting, Odds and Ends from 1939, we see a grubbed-up forest, and sad stumps of the trees that were logged. They focus our attention much more that the majestic forest landscapes in the background. The landscaped that had previously attracted European and American settlers to the West Coast. It looks like a cemetery; only singular, rickety trees could give us some hope for a rebirth.

The Iron Rolling Mill by German painter Adolph Menzel, which pictures the work at Königshütte (The King's Mill, now Chorzów), is the apotheosis of the industrial revolution. The subtitle of the painting is: Modern Cyclopes. And indeed, rolling mill workers are doing their jobs just like the mythical giants, who forged thunderbolts for Zeus in Hephaestus' workshop.

Darkness filled with steam, flickering lights, and mysterious shadows combine in a battle-like drama, depicting the struggle between human and machine. Dozens of people work at the mill. Chaos, energy, and dynamism of the scene are compounded by contrasting hues used in the piece. The painting includes many details, which show the hard and dangerous working conditions in the 19th century industrial factories. Those workers didn't have any labour rights. In the name of growth, and owners getting rich, the lives and health of thousands of people were put at risk every day. Just like today, after 300 years of industrialisation, we put the natural environment at risk.

The painting by one of the Renaissance masters, Peter Bruegel the Elder, references the myth of Icarus, as described by Ovid in his Transformations. But we might even miss Icarus, the protagonist, at the first glance. You need a second look to notice, in the bottom right corner of the painting, Icarus' legs and a few feathers in the water. Icarus is drowning, but his death remains unnoticed – the farmer, the shepherd, and the fisherman are busy with their own things.

How come Icarus drowned in the sea? His father, Daedalus, was a blacksmith in Athens, and the creator of the famous Knossos Labyrinth on Crete, where – according to mythology – Minotaur was imprisoned. As it happens in Greek myths, the fickle fate made Daedalus have to escape from Crete with his son. He wanted to do it by soaring into the air on wings, self-made of feathers, which he glued together using wax. Daedalus warned his son not to fly too high. But Icarus flew up, until Sun melted the wax, and all the feathers fell apart. The boy died, falling into Icarian Sea, which was, according to the myth, named after him.

The flight and fall of Icarus symbolise excessive ambition, and humanity's drive to realise its own goals against the natural order of the world. It also shows that with each technology, which might seemingly work for our benefit, the hubris driven human could fail, and even die.

Furthermore, in his famous piece, Bruegel also referenced a Flemish saying: "No plough stops because a man dies". Who in the world of today, where nobody has time for anything, can see the coming climate catastrophe?

Second half of the 19th century was a time of change. One of the biggest discoveries of the time was electricity. Thanks to electricity, Samuel Morse could build a telegraph, and Antonio Meucci – a telephone. Thomas Edison patented a lightbulb and a phonograph, erected the first power plant, and built the first urban electrical grid, initiating electrical power engineering. Nikola Tesla built the first electric engine. Werner von Siemens founded the first electrical engineering factory and developed the first electric tram.

Electricity became widespread. The perception of time changed, and humanity saw completely new possibilities. Thanks to artificial lightning, days became longer. In the evening, one could go to a cafe, or a concert. These types of scenes in cafes, filled with dramatic, white, artificial light, were popular to paint among the impressionists, the best reporters in the world at the time. One example is The Cafe Concert: Song of Dog by Edgar Degas, where the symbols of a new, electrified world – electric street-lamps – create a unique background.

In July of 2021, panda was removed from the endangered species list. And it's great news, without a doubt. The animal remains under strict protection, but the panda population is growing. However, climate change causes bamboo forests, the giant panda natural habitats, year by year decrease in size. Arguably, in the future, the remaining pandas will still only be able to live in the same reserves, where they are forced to live now.

Despite everything, the panda got very lucky. Currently, according to various assessments, from 5 to 500 thousands of species of flora and fauna go extinct every year. Humanity has sped up the natural tempo of extinction – it is happening between 100 to 1000 times faster. Some of the species that died out were immortalised by artists, who accompanied scientists in discovering new lands. This was the case of the legendary bird, Dodo of Mauritius, of which the last specimen was killed most likely in 1662. We now know how Dodo looked thanks to sketches, drawings, and paintings.

Komunistyczna propaganda kochała pompatyczne przedstawienia dokonań narodu radzieckiego. Taki też jest temat powyższej mozaiki. Dwóch gigantów, „kowali teraźniejszości" rozszczepia atom, którego energia ma służyć chwale ZSRR i jego ludu. Ta iście prometejska wizja podkreślała wynikający z rozwoju nauki i techniki postęp cywilizacyjny i dla wielu ludzi niosła ze sobą obietnicę uniezależnienia się od kaprysów natury i wyjścia z biedy.

Atom jako „nowy ogień” rzucił jednak także długi cień. Mozaika znajduje się na ścianie frontowej Instytutu Badań Nuklearnych Narodowej Akademii Nauk Ukrainy w Kijowie. W 1986 roku w Czarnobylu nastąpił wybuch reaktora w elektrowni jądrowej. Katastrofa przeszła do historii energetyki jądrowej. W wyniku awarii przy przegrzaniu się rdzenia reaktora doszło do wybuchu wodoru, pożaru oraz rozprzestrzenienia się substancji promieniotwórczych. Wskutek całkowitego zniszczenia reaktora skażeniu uległo od 125 000 do 146 000 km² terenu na pograniczu Białorusi, Ukrainy i Rosji, a wyemitowana z uszkodzonego reaktora promieniotwórcza chmura rozprzestrzeniła się po całej Europie. Choć ofiar śmiertelnych było niewiele, w efekcie skażenia niezbędne okazało się przesiedlenie ponad 350 000 osób. 35 lat później tereny wokół elektrowni nadal są strefą zamkniętą.

Ze względu na konieczność odejścia od paliw kopalnych energia jądrowa znów znalazła się w centrum uwagi. Naukowcy i naukowczynie są zgodni co do bezpieczeństwa dzisiejszych technologii jądrowych. Elektrownie atomowe to jedno z najmniej emisyjnych źródeł energii elektrycznej. Reakcja rozszczepienia ciężkich jąder nuklearnego paliwa nie generuje ani trujących substancji powstających ze spalania paliw kopalnych, ani dwutlenku węgla. Katastrofy takie jak w Czarnobylu czy w Fukushimie pokazują jednak wyzwania, jakie wiążą się z zarządzaniem technologią jądrową. Największym z nich pozostaje chyba jednak uczciwa debata publiczna o atomie: oparta na faktach, bez mitologizowania „nowego ognia” i bez straszenia.

Źródło: naukawpolsce.pap.pl

Galina Zubchenko, Grigoriy Prishedko, mozaika „Kowale teraźniejszości" ze ściany frontowej Instytutu Badań Nuklearnych Narodowej Akademii Nauk Ukrainy w Kijowie, 1957 r., fot. Yevgen Nikiforov (z serii "Ukraińskie mozaiki radzieckie")